This becomes

a problem with slender pins and more especially when handling very slender ‘micro’ pins with forceps; the

structural integrity of a tiny insect is not great and neither is the surface area of the insect in contact with

the pin and so the result is that with the smallest amount of springing back into a straight configuration after

the pin has been accidentally ‘twanged’ the insect, or the greater part of it, is launched, generally in some

lateral direction at a speed that renders its flight invisible and its destination unfathomable, fragmented and

lost forever. When this happens it will generally involve one of the rarer or more prized specimens. Fortunately

these micro pins are not strictly necessary for beetles although they are occasionally used by those skilled in

such things or where a specialised mount is needed or by the incredibly optimistic. Our tiny specimens are usually

pasted onto cards or points which are then pinned. Micro pins are generally destined for other insect orders but

in the interest of being comprehensive a well-known series of such pins will be considered.

This becomes

a problem with slender pins and more especially when handling very slender ‘micro’ pins with forceps; the

structural integrity of a tiny insect is not great and neither is the surface area of the insect in contact with

the pin and so the result is that with the smallest amount of springing back into a straight configuration after

the pin has been accidentally ‘twanged’ the insect, or the greater part of it, is launched, generally in some

lateral direction at a speed that renders its flight invisible and its destination unfathomable, fragmented and

lost forever. When this happens it will generally involve one of the rarer or more prized specimens. Fortunately

these micro pins are not strictly necessary for beetles although they are occasionally used by those skilled in

such things or where a specialised mount is needed or by the incredibly optimistic. Our tiny specimens are usually

pasted onto cards or points which are then pinned. Micro pins are generally destined for other insect orders but

in the interest of being comprehensive a well-known series of such pins will be considered.

The stainless steel headless pins sold by Watkins and Doncaster must surely rank among the most comprehensive range of sizes available anywhere. They are shiny silver with an indistinct spiral effect along the shank, they are very sharp indeed and will remain so with use, and they are headless; the ‘blunt’ end looks rather crudely cut (although you will need a microscope to see this) and is sharp so the use of forceps is essential. The thinnest size, AA2, is absolutely tiny at 0.1mm (in fact the thinnest we have seen in any catalogue) and, at 12.5mm long, very springy; I tried these for dissection work and they were simply too springy. The A series at 0.14mm are better but still too springy for dissection work. The B series (0.19mm) and especially the C series (0.22mm) are in our experience ideal for messing around with dissections at powers up to X60 and no doubt beyond. We do not recommend mounting beetles on these but there are those that do and we can only admire their skill. The series goes up to the relatively massive G at a diameter of 0.45 and a maximum length of 38mm which is the same length as the continental pins but it should be said that there are larger pins on the market. This series is very versatile if a little temperamental; with a little experience they will be found to be ideal, with the introduction of foam lined boxes the larger sizes can be handled without forceps. In our experience they do not corrode, dull or blunt. Before considering corrosion we should point out that the above discussion is not an advert for these pins, we use them because one of our members used them for microlepidoptera, had a few to pass around, and so we all began to use them, a few more sizes were purchased and we have no complaints; there are many others on the market and, so far as we know, all suppliers offer micros.

Regarding corrosion it is well known that stainless steel will not corrode, but there is stainless steel and there

is stainless steel. Entomological stainless steel pins do not corrode, nor do they discolour or easily bend. We

have tested some stainless steel pins sold for purposes other than entomology and all have suffered from some of

the above, leave these alone under any circumstances. This is not to say that all entomological pins are free from

corrosion; we have seen old ‘English’ type nickel plated brass pins ringed with verdigris where in contact with the

specimen or where inserted into cork, and we have seen older type black pins corroded so badly as to fall in half

when handled. ‘English’ type pins are now discontinued (2008) but are still available from old stock while black

pins, not to be confused with modern continental pins which come in a black finish, have been unavailable for some

time. It might seem something of a fuss for the coleopterist to be worrying about corrosion when the vast majority,

if not all, specimens will be carded and, furthermore, with modern foam lined boxes the pins will not come into

contact with any dampness hidden in the cork. Chemicals added to storage containers in order to kill or discourage

pests that are likely to attack the specimens are usually volatile crystalline organics and so should not affect

pins. As a safeguard against dampness inside these containers a sample of silica gel can be included which will

absorb moisture and keep it out of the internal atmosphere, this has probably been used in general as a means of

preventing specimens of Lepidoptera (etc.) from ‘relaxing’ and losing their neatly set appearance but the

advantages of keeping things as dry as possible should be obvious. But things are not necessarily so simple as

this. It is probable that for some considerable time after starting to accumulate voucher material you will need

to open storage containers quite frequently and here the design of modern dwellings plays its part. Most modern

housing is double glazed and more or less air tight or lets the wind through like a sieve and the result in either

case is that, especially during the winter, the atmosphere is regularly humid. Pins, being colder than anything

else in an insect container, will attract condensation and hold it for some time even in the presence of silica

gel and so the opportunity for corrosion, even if the pin is holding only card mounts and labels, should be

obvious. Much paper and card sold nowadays is acidic and so when damp will react with older pins, especially

those containing copper. Modern foam-lined boxes are better as the foam, unlike cork, will not absorb moisture

and so the inserted part of the pin is safe.

Regarding corrosion it is well known that stainless steel will not corrode, but there is stainless steel and there

is stainless steel. Entomological stainless steel pins do not corrode, nor do they discolour or easily bend. We

have tested some stainless steel pins sold for purposes other than entomology and all have suffered from some of

the above, leave these alone under any circumstances. This is not to say that all entomological pins are free from

corrosion; we have seen old ‘English’ type nickel plated brass pins ringed with verdigris where in contact with the

specimen or where inserted into cork, and we have seen older type black pins corroded so badly as to fall in half

when handled. ‘English’ type pins are now discontinued (2008) but are still available from old stock while black

pins, not to be confused with modern continental pins which come in a black finish, have been unavailable for some

time. It might seem something of a fuss for the coleopterist to be worrying about corrosion when the vast majority,

if not all, specimens will be carded and, furthermore, with modern foam lined boxes the pins will not come into

contact with any dampness hidden in the cork. Chemicals added to storage containers in order to kill or discourage

pests that are likely to attack the specimens are usually volatile crystalline organics and so should not affect

pins. As a safeguard against dampness inside these containers a sample of silica gel can be included which will

absorb moisture and keep it out of the internal atmosphere, this has probably been used in general as a means of

preventing specimens of Lepidoptera (etc.) from ‘relaxing’ and losing their neatly set appearance but the

advantages of keeping things as dry as possible should be obvious. But things are not necessarily so simple as

this. It is probable that for some considerable time after starting to accumulate voucher material you will need

to open storage containers quite frequently and here the design of modern dwellings plays its part. Most modern

housing is double glazed and more or less air tight or lets the wind through like a sieve and the result in either

case is that, especially during the winter, the atmosphere is regularly humid. Pins, being colder than anything

else in an insect container, will attract condensation and hold it for some time even in the presence of silica

gel and so the opportunity for corrosion, even if the pin is holding only card mounts and labels, should be

obvious. Much paper and card sold nowadays is acidic and so when damp will react with older pins, especially

those containing copper. Modern foam-lined boxes are better as the foam, unlike cork, will not absorb moisture

and so the inserted part of the pin is safe.

It is probably safe to say that all modern entomological pins, used as intended, will not corrode and that this attribute is due to their composition and the quality of their manufacture rather than, in the strictest terms, the environment in which they are used. When great care is taken older pins may be considered more or less permanent structures but it should be realised that the opportunities for corrosion are not always obvious and are probably always present.

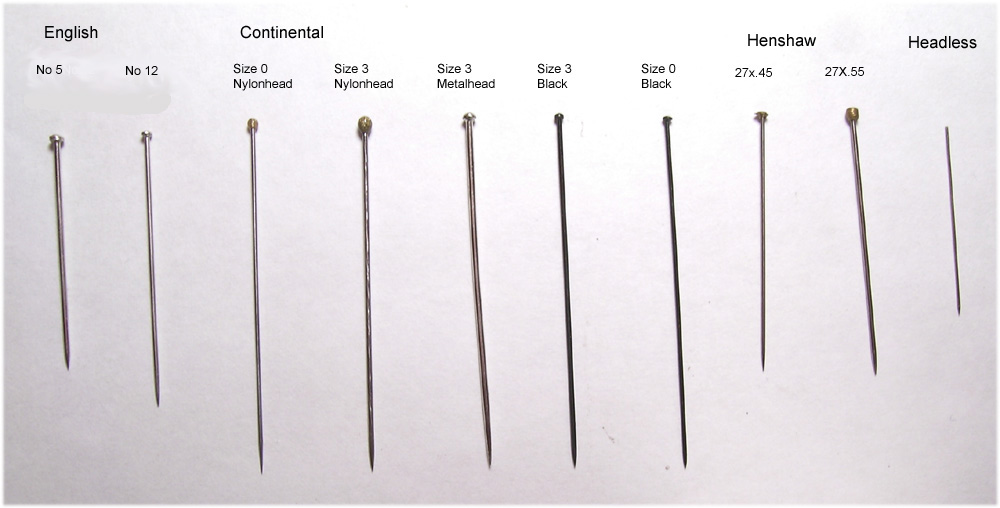

Sharpness is something that becomes obvious only when switching from one type of pin to another. Sharpness is here used to describe two aspects of pin design, firstly the acuteness of the point and secondly the nature of the shaft which should be, but has not always been, parallel. Compared with most modern pins the old ‘English’ number fives and twelves seem positively blunt, all the more so to older coleopterists who have experienced the change from ‘English’ pins in cork to a modern substitute in foam. English pins could also be very inconsistent, in some cases they had a barely perceptible thickening behind the point so that after passing through a card the resulting hole was very slightly loose on the shaft of the pin with the result that it could be moved laterally with no effort at all, the thought of cards spinning and specimens shearing off against other cards is not a pleasant one. A handy tip picked up through years of handling these pins by fingers and working with cork-lined boxes is to use a small piece of elastic band, 15-20mm long, doubled over between the fingers to pick out or insert the pins, when pressure is eased the band remains between the fingers and the pin is released. At some time or other the coleopterist will have the rather dubious pleasure of accidentally inserting a pin into a finger or thumb and the old English pins, being not too sharp, took some forcing and so, when they finally did penetrate, they tended to rocket straight down to the bone. By comparison modern sharp pins are almost a delight. Experience soon rids a coleopterist of this habit.

The majority of pins offered nowadays are of continental length i.e. 38mm and in a range of diameters, the thinnest we have seen are 0.25mm which seems a bit precarious at 38mm but all the continental pins we have examined from a wide range of suppliers (go to the AES exhibition) have been either acceptably sharp or very sharp and so, used with foam, these should be strong enough. In fact all of the continental pins we have seen seem to be of very high quality. An exception to the 38mm length is the javelin-like continental number seven, at 50mm long and 0.7mm thick (from Watkins and Doncaster). We have seen this used only once, to accommodate a huge puss moth and even here the top 10mm or so was bent at a right angle to allow it to fit into a cabinet drawer. Continental pins are available in a range of designs, some of which are very attractive, they are all of stainless steel although black designs are available in enamelled stainless steel. Some have moulded round or flat head. Large or small, heads and some have round nylon heads. They are made by a fair number of companies and so it is a good idea to obtain samples before deciding upon a type to use. Both Henshaw and Lydie Rigout (who supply Hillside pins as well as Japanese models, etc.) stock excellent quality pins. Czech pins are also supplied by Lydie Rigout and at another AES stall we found, but did not have a chance to examine, Polish pins.

We have read elsewhere that specimens mounted high up on continental pins may be safer from some of the pests that destroy specimens and experience elsewhere may have shown this to be true. It seems unlikely though that anything capable of climbing a pin in order to reach a specimen will be reluctant to go the extra five or ten millimetres in order to obtain a meal. (Vertigo?)

As well as stainless steel headless and continental types there are a few other types offered by various or

individual suppliers. In my own case I do not like deep boxes and so continental pins are not an option which meant

that when the 25mm (No5) English pins became unavailable I needed to find a replacement. The nearest I could find

was a Chinese model (27x0.56mm) from Henshaw. This also comes in a thinner version (0.45mm) which is ideal for the

tiny card points from the same supplier, and in a range of lengths; 27, 30, 33 and standard continental, 38mm. They

are stainless steel, very sharp and have a curious wire wound soldered head which is bronzy in appearance, looks

good and provides a decent grip for those who do not habitually use pin forceps. They are also reasonably priced

which brings me on to another aspect i.e. cost. You really do need to look through as many catalogues as possible

in order to realise that some pins are very expensive; the cost of a hundred may seem ‘a bit steep, but o.k., I’ll

wear it because they’re good quality,’ but look up the VAT and postage situation as well and realise that you may

well need to buy a considerable number in the future. An ostensibly good choice may seem on reflection of such

considerations not so clever after all. Realise also that continental pins will require more expensive deep store

boxes which will also take up more shelf space.

As well as stainless steel headless and continental types there are a few other types offered by various or

individual suppliers. In my own case I do not like deep boxes and so continental pins are not an option which meant

that when the 25mm (No5) English pins became unavailable I needed to find a replacement. The nearest I could find

was a Chinese model (27x0.56mm) from Henshaw. This also comes in a thinner version (0.45mm) which is ideal for the

tiny card points from the same supplier, and in a range of lengths; 27, 30, 33 and standard continental, 38mm. They

are stainless steel, very sharp and have a curious wire wound soldered head which is bronzy in appearance, looks

good and provides a decent grip for those who do not habitually use pin forceps. They are also reasonably priced

which brings me on to another aspect i.e. cost. You really do need to look through as many catalogues as possible

in order to realise that some pins are very expensive; the cost of a hundred may seem ‘a bit steep, but o.k., I’ll

wear it because they’re good quality,’ but look up the VAT and postage situation as well and realise that you may

well need to buy a considerable number in the future. An ostensibly good choice may seem on reflection of such

considerations not so clever after all. Realise also that continental pins will require more expensive deep store

boxes which will also take up more shelf space.

As well as entomological pins most suppliers offer attractive ‘points’ or ‘lills’ for laying out labels in boxes or drawers, and plastic headed, very visible, pins for other work e.g. setting or holding specimens down for dissection.

Most suppliers are happy to send a sample of their pins and it is well worth looking at a few different types before any decision is made.

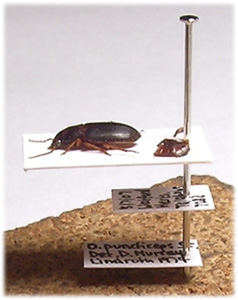

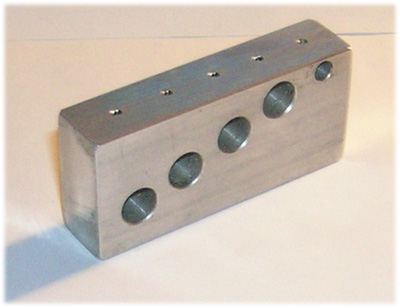

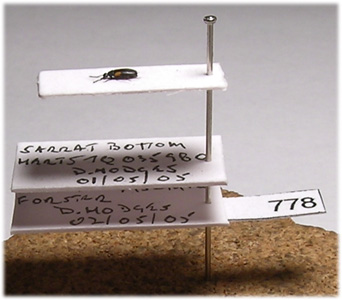

Along with mounting a specimen a pin must also hold a couple of data labels and a pin of only 25mm length is quite

adequate for this although these labels will be more visible on a longer pin. To arrange these neatly a pinning

stage will be needed to give standard heights, as well as producing an aesthetically pleasing arrangement this

will make the arranging of a series of specimens for viewing under a microscope a much easier task. Things must

be arranged on the pin in a practical way; enough room must be left to accommodate forceps or fingers without

risking damage to the specimen. In one collection we have seen room is left under the specimen card and above the

first data label to allow access for forceps, all on a 30mm pin, it sounds impractical but in practice works well,

the big drawback being that room must be left between rows of specimens to allow access with forceps. Entomological

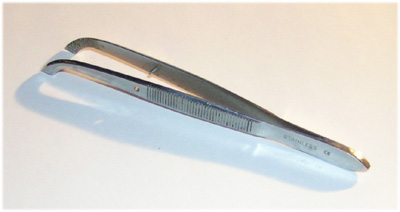

forceps will be the preferred way of handling pins for most workers, these forceps are curved, splayed and have a

moulded grip on the closing face and, with a small amount of experience, may be used with confidence. They quickly

become very good for placing specimens into boxes vertically, even among a densely arranged collection. When

starting out a great deal of moving around of specimens will be necessary and so it will essential to become adept

with these forceps. Also it is as well to realise that if you are at all serious about the subject your collection

will outgrow your containers and arrangements so do not be too fussy about labelling boxes; to do this correctly

you will need to print off lots of different labels with different fonts etc, and it is remarkably difficult to get

everything square and in straight lines; to spend lots of time furnishing a box like this to produce what is

essentially a work of art only to see it become redundant through obtaining more species is very frustrating.

Along with mounting a specimen a pin must also hold a couple of data labels and a pin of only 25mm length is quite

adequate for this although these labels will be more visible on a longer pin. To arrange these neatly a pinning

stage will be needed to give standard heights, as well as producing an aesthetically pleasing arrangement this

will make the arranging of a series of specimens for viewing under a microscope a much easier task. Things must

be arranged on the pin in a practical way; enough room must be left to accommodate forceps or fingers without

risking damage to the specimen. In one collection we have seen room is left under the specimen card and above the

first data label to allow access for forceps, all on a 30mm pin, it sounds impractical but in practice works well,

the big drawback being that room must be left between rows of specimens to allow access with forceps. Entomological

forceps will be the preferred way of handling pins for most workers, these forceps are curved, splayed and have a

moulded grip on the closing face and, with a small amount of experience, may be used with confidence. They quickly

become very good for placing specimens into boxes vertically, even among a densely arranged collection. When

starting out a great deal of moving around of specimens will be necessary and so it will essential to become adept

with these forceps. Also it is as well to realise that if you are at all serious about the subject your collection

will outgrow your containers and arrangements so do not be too fussy about labelling boxes; to do this correctly

you will need to print off lots of different labels with different fonts etc, and it is remarkably difficult to get

everything square and in straight lines; to spend lots of time furnishing a box like this to produce what is

essentially a work of art only to see it become redundant through obtaining more species is very frustrating.

Given the quality of modern entomological pins the final choice will be one of personal preference based on aesthetics and also perhaps cost. The feeling I get nowadays, and for some time past, is that there might be a shift towards continental style pins but this is based mostly on what is offered in the catalogues and might not apply so generally to coleopterists; longer pins are more convenient when double mounting i.e. using the longer pin to support a foam or polyporous mount which in turn supports a micro-pinned specimen. At the time of writing the price of pins varies between just over a penny and about five pence each, they are generally sold by the hundred but some suppliers also sell them by the thousand and so offer savings. Our earlier comment about VAT should considered as some catalogue prices include it and some do not, postage rates vary considerably and so must also be considered.